The Bloomingdale Trail, or The 606, opened just over a year ago, replacing an old railroad track on the northwest side of Chicago with an elevated garden/walking, jogging, rollerblading/community gathering spot.

While some neighbors worried about rising home values pushing out longtime residents, others were excited for their neighborhood. Whatever side one takes, trails like The 606 are the current favorite urban planning tool for many cities. Trails like those in Atlanta, Washington, DC, and Los Angeles are “placemaking” projects designed to drive economic development and improve quality of life, and in many cases to reconnect disconnected neighborhoods and draw back the middle classes—and their taxes—to cities’ cores.

In the coming weeks we’ll release a report on the impact of The 606 on nearby housing prices. In advance of that, we wanted to highlight similar paths across the country and their varied goals for urban design and concerns about their impact on the surrounding communities and neighborhoods.

The granddaddy of “rails-to-trails” projects is the High Line in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City. Since the first segment opened in 2009, it has attracted luxury developers and contributed to skyrocketing housing prices, a warning sign for other cities to pay attention to the need to preserve affordable housing.

In addition to The 606 in Chicago, two new greenways are in the works. The Paseo Trail is a four-mile stretch slated to connect Pilsen and Little Village, two predominantly Latino neighborhoods on the southwest side of the city. The first part of the path runs along Sangamon Street from 16th to 21st streets. Much of the trail will replace at-grade abandoned tracks, which the city bought from BNSF Railway. Funded by a mix of local and federal funds, the trail will include gardens and art celebrating Latino culture. Local leaders insist it has little in common with The 606, but it raises similar concerns among neighbors: price hikes and displacement in an already-gentrifying area. The announcement of the project last spring was followed by a housing fair, where the city distributed information on preserving affordability.

A park and trail system is also slated to replace two miles of an unused, elevated rail line in Englewood, a struggling, predominantly African American neighborhood on Chicago’s southwest side. The centerpiece of the envisioned trail is a “festival plaza and market,” populated by local businesses. Called the New ERA (Englewood Remaking America) Trail, it is still in its early stages, though the proposal already points out that the vacant land nearby is ripe for redevelopment.

Equity efforts are topline in Washington, DC’s, Bridge Park, expected to open by late 2019. The elevated path connects the relatively affluent Capitol Hill neighborhood to the distressed Anacostia neighborhood. Bridge Park will have performance spaces, playgrounds, and classrooms for environmental education. While the goal is to promote diversity and mobility among groups, low-income residents fear being priced out of their communities. During public hearings, residents recommended creating a community land trust and said job opportunities topped their wish lists. The final plan for the park includes strategies to address their concerns. Neighboring residents will be prioritized for construction and park jobs. The city will also provide down payment assistance to residents and may use the area as a pilot site for an affordable housing preservation program.

The most ambitious rails-to-trails project to date is the Atlanta BeltLine, a path for bicyclists, pedestrians, and streetcars that circles the southern city. The $4.8 billion, 22-mile trail is expected to be completed in 2030, but about half is already open to the public. Trails and parks, including nearly seven miles of remediated brownfields, will jut off from the primary path. The path connects dozens of diverse neighborhoods (touching nearly one-fourth of Atlanta’s population), directly or through new transit lines. The city, county, and school district lead the project and have created a public-private partnership to help raise funds. Unlike some of its sister projects across the country, the BeltLine not only attempts to preserve affordable housing, but promises 5,600 new units through land acquisition and incentives for developers. The ultimate goals, Paul Morris of ABI, the entity formed to oversee the BeltLine project, told an audience at DePaul last December, is to get people to unite in a city that has historically been divided. This is “the largest social experiment in the city’s history,” he said.

Miami’s Underline will not convert a railway but rather the area underneath it—specifically 10 miles under MetroRail from Miami River to Dadeland South Station. The bike and pedestrian path will have amenities tailored to the needs of communities it runs through—a playground in a neighborhood without one, for example. One stated goal of the project, which has public and private funding, is to attract development. Real estate developers have already contributed $75,000 to the Underline, which is designed by the same firm as the Highline and is set to break ground in 2017.

A bright orange boardwalk lines Newark’s Passaic River, the first such pedestrian access to the area in decades. The communities neighboring the new Riverfront Park have been victims of urban renewal efforts gone wrong, and the river was the site of toxic chemical dumps. Now, there are parks and exercise classes along the path, the product of an effort facilitated by a community development corporation. But the neighbors haven’t forgotten the tumultuous past. The county, state, and federal government poured about $25 million into building the boardwalk and surrounding amenities, but cleaning up the river and making sure the neighborhoods benefit from the project is still an uphill climb. Community organizers involved in the project have said it is on the right track but more work needs to be done to keep low-income residents in the neighborhood.

Though not a trail, another project in the Chicago region that will surely transform the Southside neighborhood is the Obama Presidential Center. In July, the President announced Jackson Park as the location for the center. The park runs parallel to the lakefront beginning just south of the Museum of Science and Industry and near the University of Chicago.

"I think it's a benefit to the South Side of Chicago, period," U.S. Rep (D) Robin Kelly told the Chicago Tribune. "It's good for the South Side and uplifting to have a presidential library there." Others, however, worry about gentrification pressures in the nearby Woodlawn neighborhood, akin to those along the 606 Trail. Woodlawn is a predominantly African American neighborhood that is feeling some twinges of gentrification.

Each of these greenway projects is too new to allow for conclusions about the effect on the surrounding neighborhoods and housing stock. But concerns over displacement and equity are front and center for many projects. The balance between attracting growth and investment, which cities need to survive, and the risk of displacing those with less income and clout, is one that few cities have as yet managed successfully.

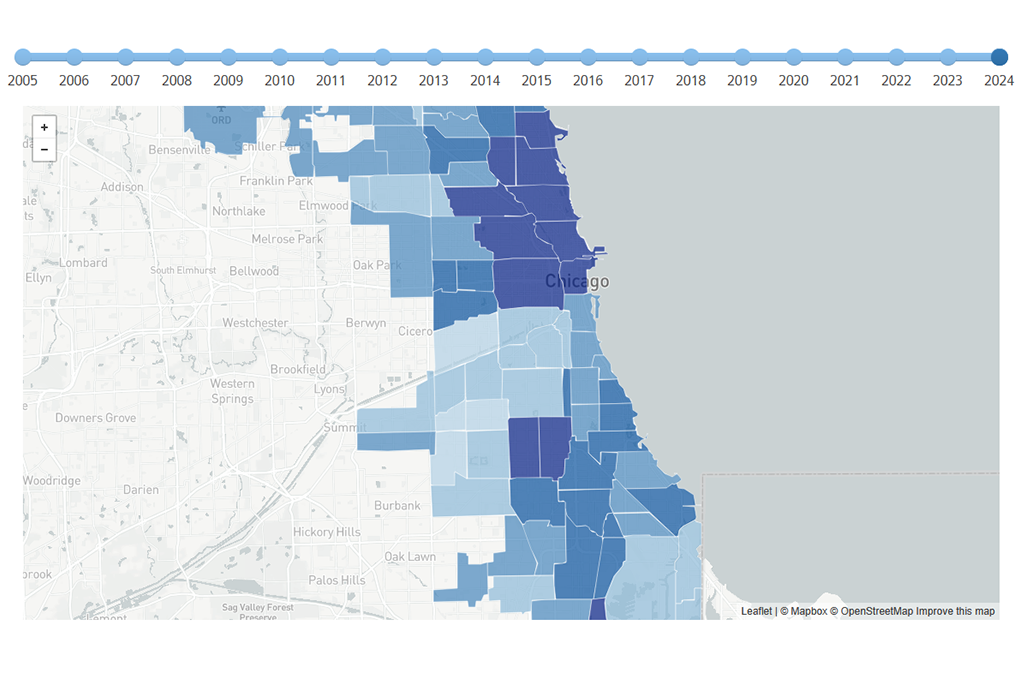

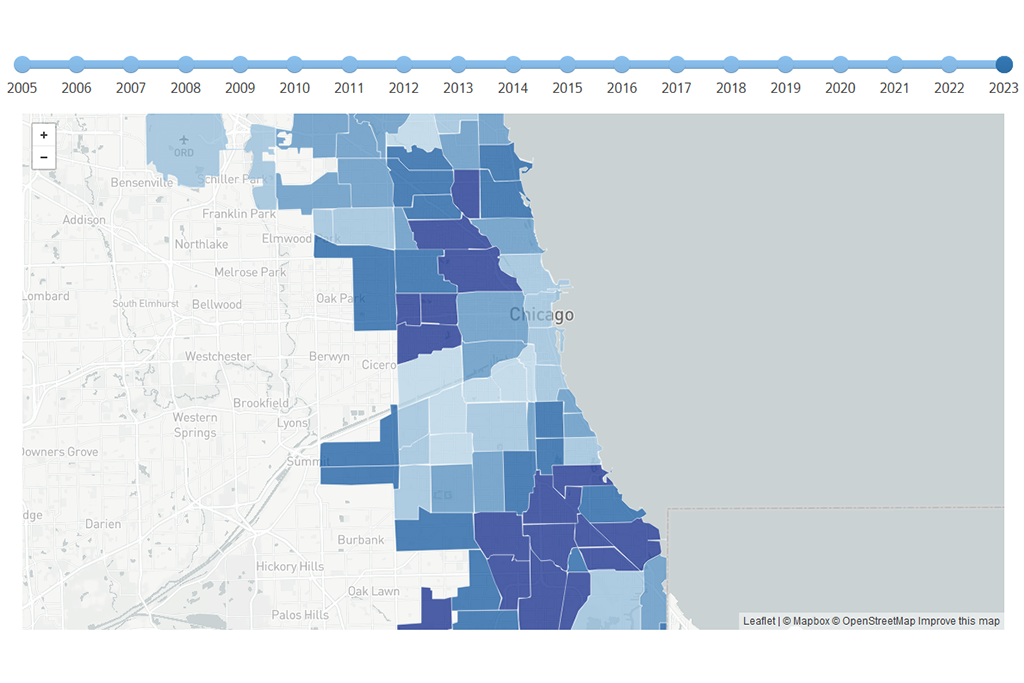

Our analysis of The 606 will highlight how housing market conditions changed in the area around the trail after work began, what type of premium people were willing to pay for homes near the trail, and how these factors varied based on the economic and demographic characteristics of the surrounding communities. Stay tuned!

Photo/Payton Chung