Property has been one of the surest ways to create wealth for centuries, as the economist Thomas Piketty makes clear in his book “Capital in the 21st Century.” More so than hard work, land ownership has allowed people to accumulate enough wealth to pass on to the next generation. In the United States, where real wages have lost ground to inflation since the late-1970s, housing has been the saving grace. For most Americans, homes are still the top asset. With every payment of principal on a mortgage, homeowners build equity. And housing prices generally appreciate. The conventional wisdom has been that home prices will appreciate by 4 percent to 5 percent per year. Piketty traces appreciation over centuries and finds the same average annual rate of return.

But as we all know by now, housing prices do not eternally rise. Inevitably, there are periodic “adjustments.” So what does that mean for families who happened to buy in the years before one of those adjustments—say in 2000?

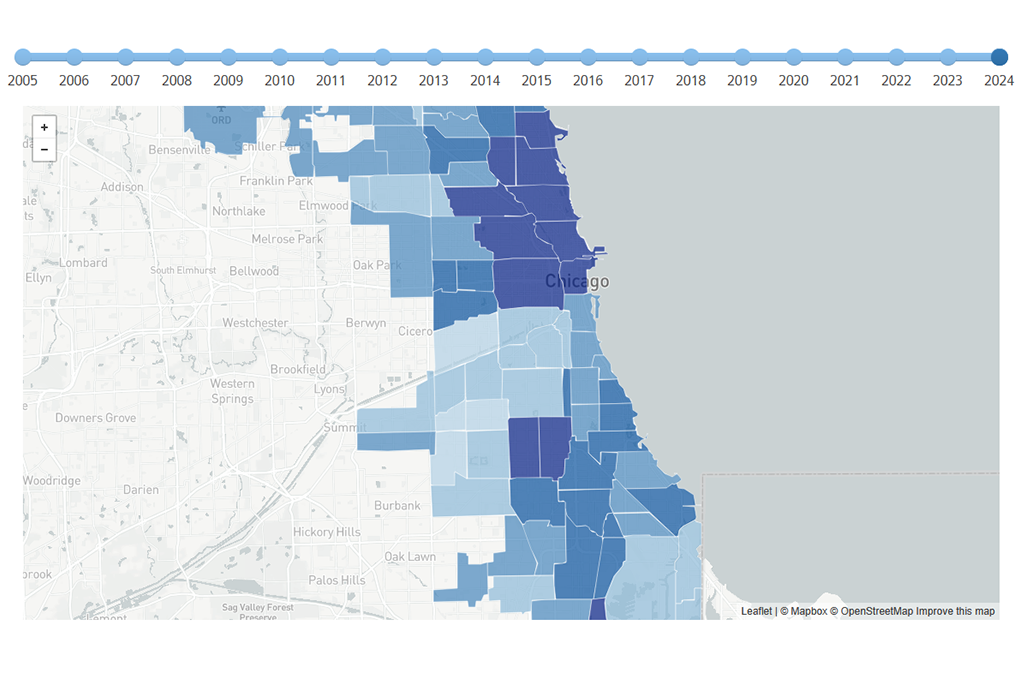

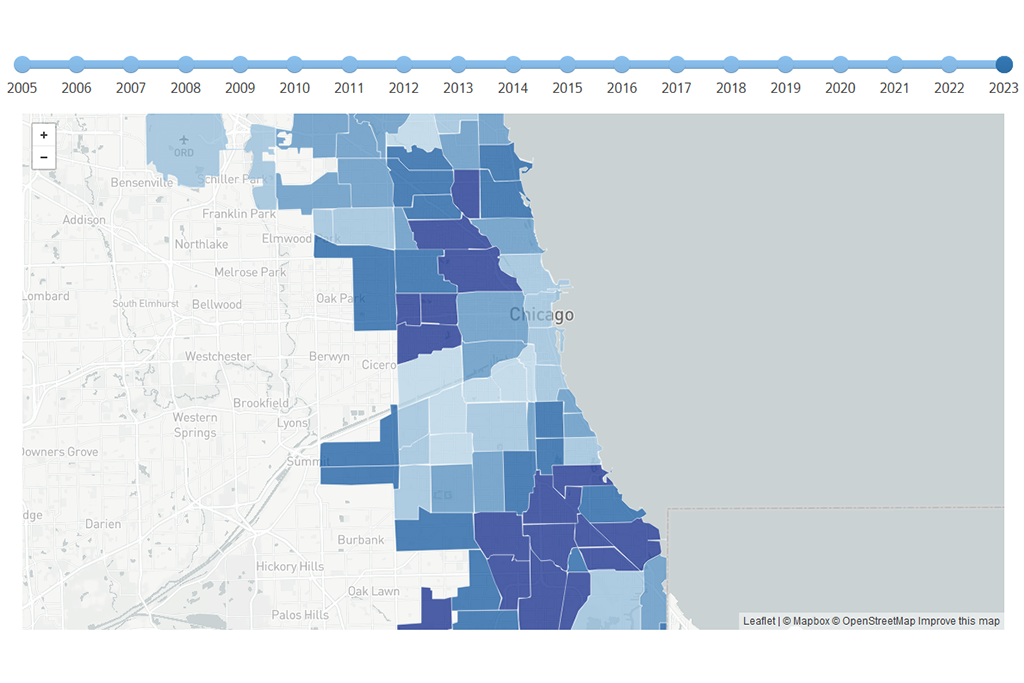

Our recently released Cook County House Price Index looks at that question by examining the change in housing prices from the first quarter of 2000 through the fourth quarter of 2014 in Chicago neighborhoods.

The report illustrates the impact on two hypothetical families, both of whom buy a house in 2000. The first family buys their house for $320,000, the median value properties in West Town at the time. West Town includes Wicker Park and Ukrainian Village and had a median household income in 2011 of $64,664. The second family buys a home for $85,000, the median value of properties in 2000 in Auburn Gresham, a neighborhood on the city’s southwest side with a median household income of $33,663 as of 2011.

During the housing boom, both properties appreciated substantially. But when 2007 hit, the price of a home in Auburn Gresham plummeted while home values in West Town fell less dramatically. The recovery for the West Town house started in the second half of 2011, two years before any recovery in Auburn Gresham.

Assuming both families did not take on added mortgage debt, the house in Auburn Gresham today is worth $86,500, only $1,500 more than in 2000, before the rise, bust, and rise of the market, for a rate of return of zero. Any equity in the home was built solely by paying down the mortgage principal.

Meanwhile, the house in West Town has more than doubled in value (a 119 percent increase) and appreciated to nearly $700,000. On top of any principal paid down on the mortgage, the owners have built an additional $380,000 in home equity.

Of course, this example removes all the complexities and variables of home ownership that could have changed the circumstances for these two imaginary families. But it illustrates the main takeaway: some homeowners have had the chance to build equity and wealth during the last 14 years, while others are back in 2000 where they started (other than any principal they have paid down on the mortgage).

Those on the unlucky side of the equation are too often those in low-income communities or communities of color, thus undermining the very people who most rely on housing to generate wealth. The Urban Institute has found a larger share of the wealth of young families and families of color stems from home equity relative to white and older families, whose wealth comes from a more diverse portfolio including retirement savings or stocks and bonds, equity in businesses, as well as equity in homes. In part as a result, during the Great Recession, African American and Hispanic families lost 47.6 percent and 44.3 percent of wealth, respectively, compared with a 26.2 percent loss for white families.

One thing is clear, without looking closely at community-level trends, we risk overlooking these disparities and missed wealth opportunities. An overall improvement in the housing market is not necessarily an improvement for all, particularly those who are waiting for clear signs of a recovery that more affluent areas are already enjoying.

Photo/Eric Allix Rogers